D A N S - c i t É

PERCEIVING DENSITY AND REIMAGINING URBAN LIFE IN SOUTH BOSTONCollaboration with Emerald Wu, Ethan Levine, & Yen PhoawSpring 2016Instructed by Carles MuroPublished & exhibited in GSD Platform 9Cities are extremely complex social and spatial organizations. The city is made of its streets and its squares, its blocks, and its buildings, but also of its dwellers. This project investigates the spatial organization of the city, and its effects on dwelling, and explores the role of housing as a central component of the physical fabric of the city and the fundamental site of the negotiation between the individual and the collective. Dwelling, both in the individual and collective realms, informs a larger conversation about density. What are we talking about when we talk about density? The traditional understanding of density (as the number of people per unit area, or the floor to area ratio, etc.) implies a quantitative metric of city-life but fails to capture the rhythm of the art of inhabitation. The notion of an actual versus perceived density became the conceptual tool used to frame the problematique. The concept of perceived density brings to light the intuition, sense, and experience of city dwellers and is parameterized through such factors as building type, facade articulation, transient population crowding, topography, tree line height, traffic noise, light penetration, etc. In light of the contemporary challenges of housing and urbanization, this expanded notion of density provides for diversity and well-being in a reimagination of urban life in South Boston.

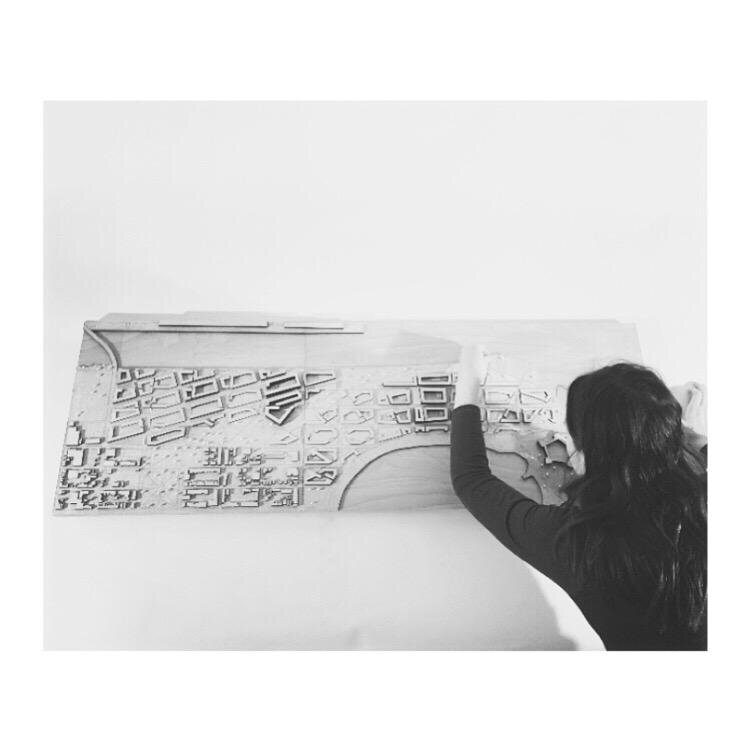

The project involves an understanding of two forms of urban densifiers: people and architecture. The approach is to counterbalance density caused by transient population through FAR. That is to say that in areas of high civic program clustering (proposed T line stops, public institutions, recreation, etc.), the housing component would be restricted through FAR and vice versa. The variance in FAR creates a gradience in building topography - low-rise (2-4 floors), medium-rise (4-8 floors), and high-rise (8-16 floors) - which naturally results in a variation of typology.

The majority of housing units are configured into three-dimensional “L” shape units that provide both street and courtyard views which, in combination with the unit shape, quite literally reorients the dweller’s perception to and from the city. The building typology is informed through the process of offsetting the modules of each unit to increase surface area of collective space (e.g. balconies, patios, etc.) and to intensify the types of spaces in the interior. The high-rise building has a zero foot offset to maintain its tower typology and reduce the articulation of the unit in the facade as this building type already has a high perceived density. The mid-rise type has a five foot offset which allows for a small balcony and study to be introduced in the thick space created between the shifted module and the stair element that cannot be moved in order to meet the module above. The low-rise type has a ten foot offset which lends itself to a densified matte typology. The ten foot shift allows for structural integrity while providing for, say, a whole new bedroom in its new thick space. At its smallest scale, the offsetting became an architectural tool used to quite literally densify these habitations in terms of activity and use and users. At the large, urban scale, the dialectic between the discrete and the continuous, the individual and the collective, people and architecture, actual and perceived densities, curated new imaginaries for the art of inhabitation.